An epicenter of beauty that strikes at the universal

I was in high school when I first saw Keisuke Serizawa’s work; the morning news reported that an eponymous exhibition held at the Grand Palais in Paris [1976] was a great success, with his work assessed as rivaling that of Paul Klee. There on the screen I saw a poster in which the Chinese character 風 (wind) was drawn with a touch that differed both from calligraphy and from Japanese emblem designs, and the name Serizawa was written in Roman letters below, shining brightly. I remember feeling that surely this would have popular appeal around the world.

The next time I came across Serizawa’s name was around the time when I had begun doing work related to Japan’s provinces; some distinguished people introduced me to his work. Two of the leading figures in their respective local cultures, Yoshiro Shio, who produced washi paper in Aoya in Tottori Prefecture, and Keisuke Yoshida, who ran a washi studio called Keijyu-sha in Yao in Toyama Prefecture, were both trained by Serizawa in their youth. Each managed a washi museum in a relocated and reused elementary school building, where they used similar exhibit furniture and fixtures to display washi as well as artwork and crafts from all corners of the world.

When thinking of mingei (folk art), the first person to come to mind is Soetsu Yanagi. Believing and advocating that beauty was found not in works by artists, but in the tools and utensils of daily life, cultivated in the context of everyday life and produced by those who are anonymous, Yanagi encouraged those who were engaged in the creation of traditional crafts like ceramics and washi. Serizawa was among the artisans who embraced this ideology of Yanagi's, and, as his katazome stencil dyeing was the ideal embodiment of the mingei Yanagi espoused, everyone involved in the mingei movement was enthralled with his work.

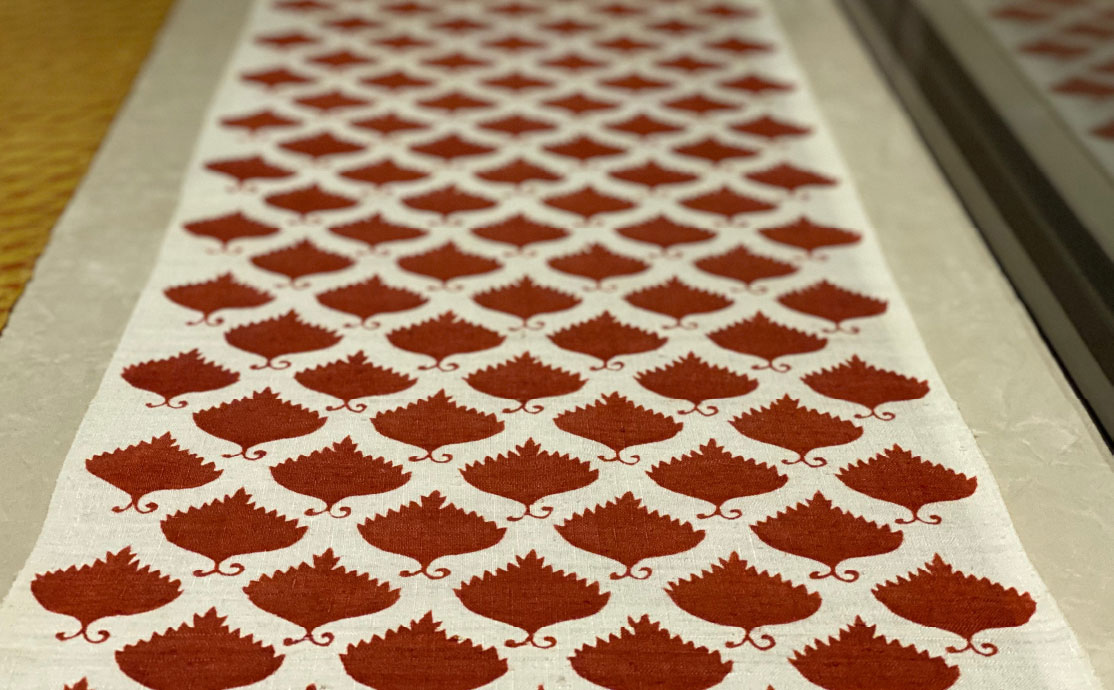

In katazome, a sketch is reproduced as a stencil cut out with a delicate knife. A resist paste is then applied, and the material, mainly cloth, is then dyed through the stencil. In the process of being turned into a stencil, the vivid lines of the drawing are relatively sublimated, and take on a universal form. As a result, Serizawa established his own distinctive style. His work and artistry transformed all visual elements, including hiragana (one of the Japanese syllabaries), kanji (Chinese characters) and drawings, into universal and fascinating shapes.

The 1976 TV news item reported that the Serizawa spell had reached as far as Paris. Even though I am a designer, ever since I aspired to the profession, I had deliberately avoided seeing Serizawa’s work. In Japan, there are traditional graphics with extremely high levels of perfection, like the family crests and the designs on samurai battle flags, and Serizawa’s work was among those examples of perfection in design. So I intuitively supposed that if I too were overly affected by that charm, my ability to create new shapes would be inhibited.

However, for a certain project, I was asked to explain the appeal of Keisuke Serizawa from a design standpoint, which led me to visit the museum in Shizuoka. I stood face to face with the works in the museum and was reminded of their magnificence, but it was the Keisuke Serizawa House that gave me the opportunity to sense this artist anew. By coming into contact with and directly experiencing this house, where the very breath of the artist retains a marked presence, it was as if I were releasing a seal; I was able to calmly and naturally face his body of work, and now, I honestly and keenly feel its merit in my soul.

The Keisuke Serizawa House is a private storehouse built using the itakura construction method, one used to build shrines and grain warehouses since ancient times in Japan. This structure was once relocated by Keisuke Serizawa from Miyagi Prefecture to Kamata in Tokyo. It was then moved again and reconstructed in the area adjacent to the museum in 1987. This house, “common like a peasant, healthy like a peasant”, as Serizawa once described himself, is itself a concise example of mingei. Filled with furniture, pieces of woodworking, dyeing and weaving as well as toys and fascinating handicrafts from around the world, gathered by Serizawa, who was an exceedingly avid collector, the house emits a brilliance rivaling that of the museum.

The museum was designed by Seiichi Shirai, a genius in the world of architecture. It is the last work of the architect, whose 1955 Temple of Atomic Catastrophes, though unfinished, introduced a style that sought a coherent spirituality in Japan’s contemporary architecture. The architecture of the sekisuikan, as he called the museum, with a pond and a fountain in the courtyard, is characterized by arched windows and narrow apertures resembling arrow loops. Due to the need to shield the displays from ultraviolet rays, unfortunately one cannot see the outside from the inside, but the maze-like interior and the stonework exterior further add to the building’s appeal.

Adjacent to the art museum are the Yayoi-period dwellings of the Toro Remains. Today, it is like an open-air ancient history museum with recreated pit dwellings. Pit dwellings are said to have been invented in the Jomon period before the Yayoi period, and could be called the source of folk art. With embankments to prevent water intrusion and granaries on stilts built on the side, they are worth a visit as they form the foundation of the Japanese private houses of the settlement era with rice cultivation as the background.

2021.4.5